The Russian assault on Ukraine casts an undeniable shadow on this year’s sedarim. Since the seder tells the story of the Jewish revolt against tyrants in the distant as well as the more recent past, I was curious: What are the opportunities, using the traditional seder symbols and texts, to bring in Ukraine to the Seder conversation? Where is Ukraine in the Haggadah?

I. THE REFUGEES

As I write, less than a week before Pesach arrives, the BBC reports that more than 10.5 million people have fled their homes, including more than half of the country’s children. 4.3 million have fled the country and another 6.5 million have been been displaced from their homes and fled elsewhere within Ukraine. Where are these refugees recalled in the Seder?

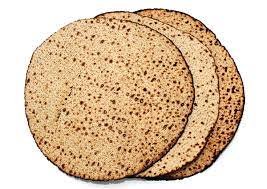

1. In the taste of the Matzah. Matzah is the food of people who have to flee their homes; of those who have to leave so quickly that there isn’t even time for the bread to rise: And they baked unleavened cakes of the dough that they had taken out of Egypt, for it was not leavened, since they had been driven out of Egypt and could not delay; nor had they prepared any provisions for themselves (Exodus 12:39).

Many of the Ukrainian refugees were forced to leave their homes for safer environs like Poland, Romania, Moldova, Hungary, Slovakia, Germany, and, for the lucky ones, the State of Israel. Many left with the clothes on their backs and barely time to grab their most precious possessions.

That is the essence of Matzah. It can be the bread of deliverance that arrives in the blink of an eye (as in Egypt), but it can also be the food of those who are forced out of their homes just as quickly (לַחְמָא עַנְיָא / “the bread of affliction” indeed).

2. In the Yachatz. We take the middle matzah and break it in half. As we do so, consider the following meditation:

We break this middle matzah and are reminded of so many divisions in our unfolding story.

Some separations are blessings: “God separated the light from the darkness” (Gen. 1:4); “God made the expanse to separate between the waters above and the waters below” (Gen. 1:7); “The waters split and Israel went into the Sea on dry ground” (Ex 14:21-22).

But other separations are tragic: Children torn from their parents in war-torn Ukraine, families displaced from their homes.

As the Matzah is broken into two pieces, we recall those refugees who have fled for their lives in just these recent weeks, and we remember that as long as tyrants commit atrocities, our world and each of us cannot be considered whole.

II. PUTIN, THE TYRANT

It’s not hard to see in Putin the same sorts of megalomaniacal tyrants that stain human history, all the way back to the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Jewish history is littered with these sorts of thugs, as the Haggadah says:

שֶׁלֹּא אֶחָד בִּלְבָד עָמַד עָלֵינוּ לְכַלּוֹתֵנוּ, אֶלָּא שֶׁבְּכָל דּוֹר וָדוֹר עוֹמְדִים עָלֵינוּ לְכַלוֹתֵנוּ

For it hasn’t been only one enemy who has risen up to annihilate us…

Us?

Yes, us. Certainly, many thousands of the Ukrainian refugees are Jews—at least before this war, Ukraine had the 10th largest Jewish community in the world. While Ukraine has a bloody and ugly history in its treatments of its Jews, there has been a Jewish presence there for over 1,000 years.

But that is only part of bigger picture.

Because the seder is also about freedom on a global scale. To celebrate Pesach is to declare: By virtue of our celebration, may others, too, be inspired towards liberation. Surely in our time, as much as ever, we must say: when some are enslaved, none of us are free.

And so, indeed, today another enemy is standing over us, threatening us all…

III. VOLODYMYR ZELENSKYY, JEWISH HERO

It is with pride tonight that we point towards President Zelenskyy, the Jewish leader of Ukraine who has made the case for freedom and justice for his country to the nations of the world.

Yet the Haggadah is famously reticent about naming human heroes. Moses’s name only appears once in the entire traditional Haggadah, emphasizing that deliverance comes only from God:

לֹא עַל־יְדֵי מַלְאָךְ, וְלֹא עַל־יְדֵי שָׂרָף, וְלֹא עַל־יְדֵי שָׁלִיחַ,

אֶלָּא הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא בִּכְבוֹדוֹ וּבְעַצְמוֹ.

Not through an angel, and not through a seraph, and not through an intermediary:

The Holy One alone, in all God’s divine glory.

So maybe we shouldn’t dwell too much on Zelenskyy?

But the inspiration of seeing this Jewish man—who carries the moral weight of family members murdered in the Holocaust—is an important part of tonight’s telling, too. For many of us, God acts in the world through human helping hands and voices of truth, like the voice of Zelenskyy.

The famous A Different Night Haggadah (eds. Noam Zion and David Dishon, ©1997) suggests a tradition attributed to Rabbi Al Axelrad at Brandeis in the 1970s: Having the family seder award an annual Shiphrah and Puah Prize to someone in the world who stood up to modern-day Pharaohs this year.

Shiphrah and Puah, you’ll recall, were the Hebrew midwives of Exodus 1, who refused to follow Pharaoh’s genocidal decree to kill Jewish baby boys. Their civil disobedience is the first act of rebellion that leads to Israel’s redemption. Today, we should consider at our seder those individuals who have stood up in the face of tyranny and oppression to be voices of hope and freedom.

Surely, President Zelenskyy carries the legacy of Shiphrah and Puah this Pesach!

IV. OUR ROLE IN THE STORY OF HOPE

There is a lot of “reminding”, “recalling”, and “commemorating” in the Seder. But our seder is incomplete if it remains in the realm of memory and storytelling. The Seder is a call, upon completing our celebration, to work and act to make the world whole again.

This is incorporated in Elijah’s Cup, symbol of the messianic hope for a future free of war and fear.

Long ago, my family adopted a well-known custom: we no longer leave Elijah’s Cup passively on our table, waiting for God to redeem us. Now we pass Elijah’s cup around the table, inviting each participant to pour in a few drops from her own glass—representing that unique responsibility of each of us to be God’s partner in the work of freedom. And so, too, should we leave this seder committed to the task:

· Giving Tzedakah to help the refugees; for instance, through the JDC, the World Union for Progressive Judaism, Beit Polska/Jewish Renewal in Poland’s Refugee Relief, HIAS, the Kavod Tzedakah Fund, or other trustworthy organizations.

· Celebrate and share the stories of those who are doing good, such as the Dream Doctors Project, an Israeli organization that has sent Mitzvah-clowns to the Ukrainian border to welcome the refugees with gentleness instead of fear. Or Tel Aviv University, who has offered full scholarships to Ukrainian students and academics displaced by the war. Or the Survivor Mitzvah Project, who have been caring for Jewish elders in the FSU for years—and remain on the ground with those Ukrainian elders who have been unable to leave.

· Urge the Israeli government to reject the far-right voices of isolationism and to accept even more refugees than they already have; insist that this is the sort of crisis for which the Zionist message rings loud and clear. (This might best be achieved with an email to your local Israeli consulate.)

· Get ready—they’re coming. The Biden Administration has called for America to open its borders to 100,000 refugees in the weeks and months ahead. Will we be ready to welcome them into our homes and communities in the spirit of safety and security?

This is what it means to bring Elijah. And that call to freedom is incumbent upon each of us this Passover. In the words of the Hasidic master Rebbe Menachem Mendel of Kotzk (1787-1859, Poland):

We err if we believe that Elijah the Prophet comes in through the door.

Rather, he must enter through our hearts and our souls.